On the morning of April 4, 1979, the military dictatorship of General Ziaul Haq hanged to death Pakistan’s first elected Prime Minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

Today is the 35th anniversary of that judicial crime.

If you are as much of a maniacal reader on the political and social history histories of Pakistan as I am, then I’m sure you’ve already noticed that after Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the second most discussed Pakistani leader in such books is Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

So much has been written about the man. His achievements and follies; his charisma and eccentricities; his accomplishments and blunders. I can’t really add more to what is already out there in the shape of whole books, papers and articles written on the man.

I was barely 6 years old when Bhutto rose to become Pakistan’s head of state (in January 1972) soon after the secession of what was once called East Pakistan.

Bhutto’s populist Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) had swept the 1970 general election in West Pakistan's two largest provinces, Punjab and Sindh, and it became the country’s majority party once East Pakistan broke away (after a violent and tragic civil war there).

I do have some memory (rather random images) of the 1971 Pakistan-India war (that followed the civil war) and of Bhutto’s first address to the nation on PTV when in early 1972 he took over the reins of a defeated and demoralised nation.

What I remember about the war are the blanket blackouts, loud sirens and terrifying sounds of artillery fire and jets zooming over our house near the coastal areas of Karachi in Clifton; and how one evening there was a huge explosion that shattered the window panes of almost every house in the vicinity after which (in the morning), the war was over (December 1971).

We trickled out of our basements and make-shift bunkers only to see a number of oil refineries visible from our house, and a series of war ships on the horizon on fire.

The flames rose so high it seemed (at least to a 6-year-old kid) that their thick black smoke was about to darken the fluffy white winter clouds hovering over Karachi.

Then Radio Pakistan announced that the Pakistan armed forces have surrendered.

But we kids were too busy collecting the smothering splinters of the bombs that had been dropped by Indian jets only miles away from our area of residence, not knowing that the country had acutely been split into two.

Bhutto was no stranger in our house. In the early 1960s my father was a Psychology major at the University of Karachi (KU) and a member of the left-wing National Students Federation (NSF).

He was also a bosom buddy of famous student radical (and future PPP minister and politician), Miraj Muhammad Khan.

Though my father came from a large, conservative business family from North Punjab, he was a rebel. He was the first in the large family to bypass studying for a business degree; the first to marry outside the family (to a ‘mohajir’ - an Economics major at KU, my mother); and the first to join journalism (instead of the widespread family business) after he graduated from the university in 1964.

Like many passionate young men and women in the late 1960s, he too became a Bhutto enthusiast and remained to be one until his death from respiratory failure in October, 2009.

When Miraj Saheb, these days himself facing health issues, called and spoke to me at length soon after my father passed away, it reminded me how in January 1972 my father returned home from the Karachi Press Club and told my mother that Miraj had told him that Bhutto would be speaking to the nation on TV.

Being just 6 years old then, today I only vaguely remember my parents, cousins, younger sister, grandparents and paternal uncles gathered in front of our Russian-made ‘Mercury’ TV set listening to that address.

In those days we were one of the few homes in the country that actually owned a TV set, so the address was largely heard by Pakistanis on the radio, in spite of the fact that Bhutto spoke in English.

It is said that the speech remains to be one of the most widely heard addresses from a head of state and government in Pakistan.

In February 1972, my father moved our family to Kabul in Afghanistan where he agreed to heed my paternal grandfather’s advice to set up offices of the family business in that city.

Instead my father became the Afghanistan correspondent of the PPP’s newspaper, Musawat.

It was a Kabul that today would seem like a totally different planet compared to what happened to this city at the end of the Soviet-Mujahideen war in the 1980s and beyond.

I remember Kabul to be a pleasant and clean city, with hordes of western tourists (mostly hippies) roaming its streets and markets.

My father became a regular visitor to a popular coffee house in central Kabul where the city’s most animated leftist intellectuals met for coffee, tea, beer and most importantly, to strike passionate discussions on the state of affairs in Afghanistan.

One day my father brought home an intense looking and stocky Afghan Pushtun for dinner. The Afghan was bald, had thick spectacles on him, chain-smoked and spoke both English and an accented Urdu. The gentleman was Sardar Daoud - the former Prime Minister of Afghanistan (1953-63) and the future President of that country.

Daoud, who was a cousin of Afghanistan’s monarch, Zahir Shah, had resigned as PM in 1963. He was also a passionate advocate of ‘Pushtunistan’ – a movement that wanted to merge Afghanistan with the Pushtun majority areas of Pakistan.

My father later told me that Daoud – who’d been banished by the monarchy and had become a radical pro-Soviet republican – befriended my father at the coffee house and told him about a ‘coming revolution in Afghanistan.’

‘Bhutto was not very happy with my friendship with Daoud,’ my father told me many years later. Bhutto as well as Pakistan’s military establishment were extremely anti-Daoud, especially due to his views on ‘Pushtunistan.’

Though we returned to Pakistan in mid-1973, Daoud would go on to topple the Zahir Shah monarchy in a military-backed coup and declare Afghanistan to be a republic (in 1974).

He was himself toppled in a communist coup in 1978.

In Pakistan, my father began publishing a radical pro-PPP Urdu weekly called Al-Fatha with another journalist colleague of his, Mehmood Sham. Al-Fatha's name was inspired by Yasser Arafat’s militant left-wing Palestinian outfit.

Now back in school in Karachi I fondly remember how small kids (especially boys) loved to imitate Bhutto’s antics as a public speaker. At first I just couldn’t understand, until I rediscovered Bhutto on TV.

Afghanistan didn’t have any TV in those days, even though I remember accompanying my parents to a host of Rajesh Khanna films at Kabul cinemas.

back in Karachi, I particularly remember one Bhutto speech on PTV that he made in late 1973 that finally made the now 7-year-old me understand what all those boys at school were up to.

It was during a public gathering in Lahore. It set the nation on fire! Drunk on passion, patriotism (and his favourite brand of whisky), Bhutto was canvassing to ask his supporters to help him regenerate Pakistan’s lost pride. To my delight, a small section of this speech can now be found in cyberspace (see below):

Another memory I have of the period is watching my father discussing the passing of Pakistan’s first genuine constitution (the 1973 constitution) with his cousins and brothers.

Later on when I entered my teens in the early 1980s, I asked my father why the Bhutto regime declared the Ahmadis as non-Muslim.

His explanation was that since Bhutto wanted to bag the support of Islamic outfits like Jamat-i-Islami and others before the historic 1974 International Islamic Summit in Lahore, ‘he threw them a bone they could get busy with and get distracted by.’

I continued disagreeing with him on this issue, and he continued defending Bhutto’s action even many years later.

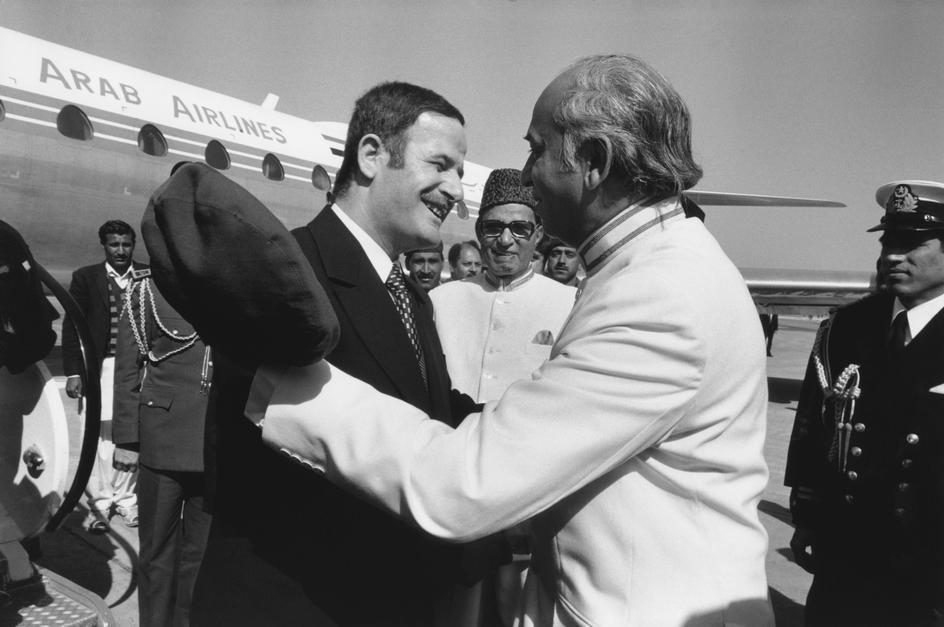

I remember the Islamic Summit very well. PTV ran a marathon transmission of the event and I also remember watching speeches by a number of leaders from various Muslim countries.

The Summit was explained as a global expression of Bhutto’s ‘Islamic Socialism’ and ‘vision’ of turning the Muslim world into a ‘third progressive force’ between western capitalism and Soviet communism.

My childhood unfolded in a very different Karachi. TV was a joy to watch (even though it was entirely one-sided); men and women were crazy about cinema as the Pakistan film industry churned out an average of 60 to 70 films a year; and people loved staying outdoors without any fear and at all hours.

Bars, nightclubs, cinemas and other recreational sites were always illuminated with bright, shimmering lights. I remember accompanying my elder cousins and their friends to the edges of the Clifton area on weekends (on bicycles) where people would gather to drink, chat, take long walks on the Clifton beach and especially eat chaat and ‘gola-gupas’.

Some would order ‘special gola-gupas’ whose liquidy chatni was laced with a heavy dose of tamarind but mixed with beer.

At this edge of Clifton was a house called ‘70 Clifton.’ This was the spacious residence of Z A. Bhutto and his family.

From 1975 onwards, when I turned 9, my father began to often take me with him to this house whenever he had to meet Bhutto.

By now he had also joined the Soviet Embassy (on Bhutto’s suggestion). Bhutto had wanted him to use his position to strengthen the media and cultural ties between the Soviet Union and Pakistan.

It was, I think, in the summer of 1975 when I first met Bhutto in real life.

I saw a very young Benazir Bhutto as well, lurking in the background; and I also remember a tall, lanky guy shaking my hand as my father stood talking to the lad in the garden of 70 Clifton. He was Murtaza Bhutto, then just 21 years old.

I found Bhutto’s wife, Begum Nusrat Bhutto, to be the warmest and closest towards my father. I would last meet this amazing woman in 1993 when (as a journalist) I made my last trip to 70 Clifton on the evening Murtaza returned from exile.

As a former member of the PPP's student-wing (PSF), I had sided with Benazir in her little tussle with Murtaza. And I continued siding with her. She was to my generation of young ‘radicals’ in the 1980s, what her father had been to the generations before us.

But the fondest ever memory of those visits with my father to 70 Clifton was of one evening in early 1976 (I was now 10) when, as my father and I entered a spacious hall, Bhutto, smartly dressed in a suit and a tie and with a cigar in hand, approached my father and with a mischievous smile loudly asked: ‘Aur Paracha! (So, Paracha); how are the Soviets treating you?’

My father smiled back and answered something to this affect: ‘Sab sahi hai, Bhutto Sahib (All’s well, Mr. Bhutto); the Soviets are fine as long as one keeps appreciating their Vodka!’

Bhutto burst into laughter.

My saddest childhood memories of the time were not exactly the shutting down of schools and the curfews that were imposed during the right-wing Pakistan National Alliance’s protest movement against Bhutto in April 1977.

Nor do I remember what I felt when I saw this weird looking military man with a strange handlebar moustache talking on PTV (in July 1977) - A man against whom I would eventually spend all of my college years fighting as a student activist in the mid and late 1980s.

A tyrant who would retard the political and social evolution of Pakistan for years to come. A man called Ziaul Haq.

My saddest memory regarding Bhutto is, of course, of April 4, 1979. I was 12 years old and now smart enough to understand what was going on.

My father had been blacklisted by the Zia regime (in 1977) and was out of a job. He still refused to join the family business.

I’d had a terrible morning at school two days before Bhutto’s hanging. My mother was summoned by my teachers and told that I would be suspended for giving a fellow student a big fat black eye! Thankfully I wasn’t.

The bugger had been waving a picture (cut out from Jang newspaper) of a cop flogging a man in public. He was mocking the flogged man, saying that all PPP supporters would be getting flogged this way.

Suddenly, bam! I smashed my fist in his face, knocking him out in 5 seconds flat. My anger was purely the result of the depression I was feeling from the economic pressures and uncertainty my family had been facing ever since the Zia regime blacklisted my father, making it impossible for him to get a job in any newspaper or magazine.

Saddest was when on the night of 4th April, some 12 hours after Bhutto’s hanging, I entered my parent’s bedroom and found my father sitting on his bed, his palms cupping his face, his head hung low, as he listened to a special programme on Bhutto on BBC Radio’s Urdu service.

I quietly sat on a chair opposite him, my knuckles still sour from punching my classmate. Then it happened. A sight I shall never forget.

My father removed his palms from his face to light a cigarette. And for the first time ever, I saw this cool, calm and stoic fellow, wiping tears from his cheeks. His eyes were swollen and red, as if he’d actually been weeping for hours.

I was stunned. I had no clue what to do. It was only then that I realised that Bhutto really was dead.

Scene after scene was related over the years in articles and books by so many people of how Bhutto’s death had actually made grown-up men and women cry.

I saw one such person do that right in front of my eyes. That evening I wanted to hug my father. But I somehow couldn’t. I just got up and left. The age of apathy had arrived in Pakistan.