As the legend goes; a torrid love affair ended when Pakistan's first Test centurion, Nazar Mohammad had to, in haste, jump out of a window upon being caught by his lover’s husband. He broke his arm as he hit the ground.

The injury also ended his career.

Cricketers in Pakistan have perhaps always been the most desired stars in the country. Women have wanted to woo them and men have wanted to be them.

Pakistan's cricket sprung off from a school and college system, supported by clubs in the bigger cities.

Most cricketers came from educated middle and upper class urban families that had the opportunity to play the elitist sport the British had left behind.

The schools nurtured Pakistan's best cricketing talent and to be the university's cricket team captain was the most prestigious position in the fraternity.

In 1952, when the first Pakistani eleven walked out to play international cricket, they were already stars — at least in their clubs or schools.

The school boy hero Hanif Mohammad, partnered by the graceful Nazar Mohammad opened the innings for Pakistan.

In their ranks were Punjab University heroes Waqar Hassan and Khan Mohammad, the eloquent writer and journalist Maqsood Ahmed; the first editor of The News (Rawalpindi), and the fearless Lahore college wicketkeeper Imtiaz Ahmed among others.

The team was lead by patrician Abdul Hafeez Kardar and spearheaded by Pakistan cricket’s first real ‘poster boy’ and nation’s heart throb, Fazal Mahmood.

The gentry of Pakistan cricket was already of a high breed and them adorning national colours in the country’s favourite sport made these gentlemen the most adored and admired band of men in the country.

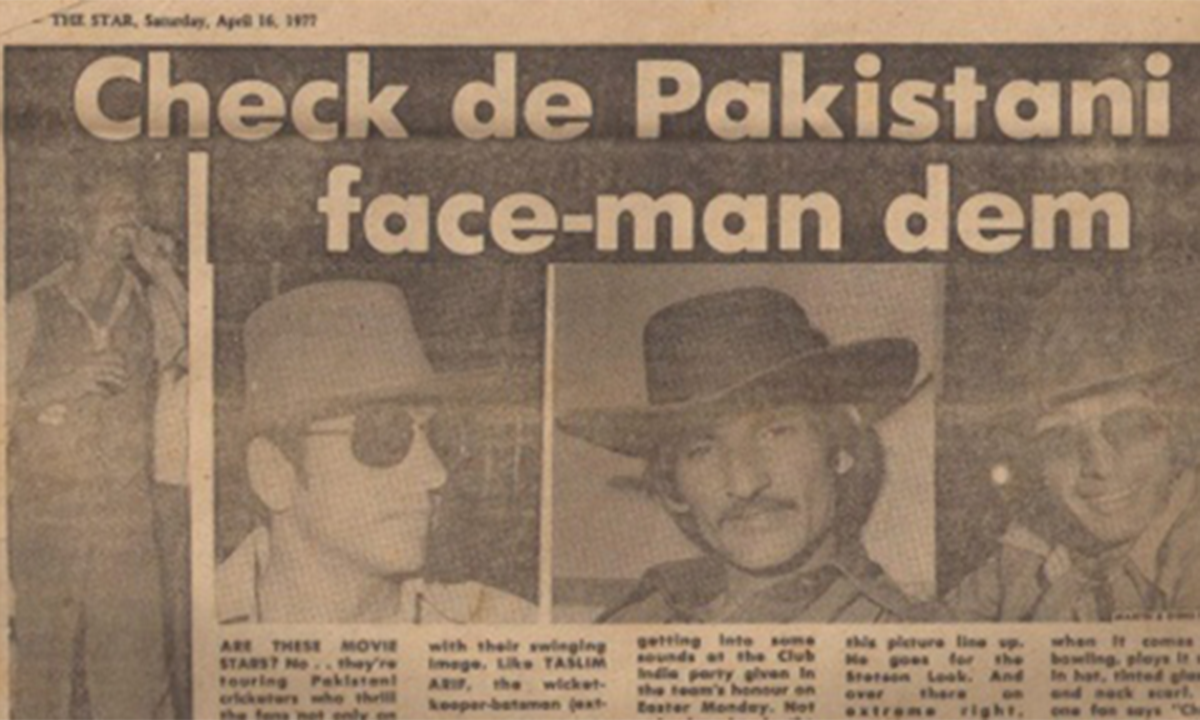

Through the years, Pakistani cricketers remained extremely popular, not just by turning out great performances on the field but also with the style and swagger they displayed off it.

Through the 60’s and 70’s the likes of Majid Khan, Zaheer Abbas, Asif Iqbal, Javed Burki, Wasim Bari, Saeed Ahmed and many others enjoyed high social status.

Many of them becoming county captains and almost all of them with a fan following that idolised them.

They were not just heroes in their own country, but had a dedicated and sizable fan club abroad, especially in the English counties they represented.

At one time, the Pakistani squad was adorned by as many as five county captains; Asif Iqbal was captain at Kent, Zaheer Abbas at Gloucestershire, Intikhab Alam at Surrey, Majid Khan at Glamorgan and Mushtaq Mohammad at Northamptonshire.

A position of great honour and dignity traditionally reserved for the noble elite; for excellent cricketers and respected gentlemen.

The female following of cricket was also sizeable in Pakistan. College and University girls turned out in large numbers to watch their heroes perform in stadiums.

However, out of all the star icons produced by Pakistan cricket, perhaps it was Imran Khan who stood out as the nation’s most loved son and eligible bachelor.

Imran was forced by the then President General Zia-ul-Haq to take back his retirement before the tour of West Indies in 1988.

Imran’s popularity can be judged in an interview taken by the late legend Moin Akhtar.

Even when he retired at the age of 40 in 1992, apart from the World Cup victory, the Pakistani public was most interested in who Imran would marry.

The media went into frenzy with talk of Imran Khan and Indian Actress Zeenat Aman’s sizzling but short-lived affair.

Soon after, Khan was married into a high socialite British family, the Goldsmith’s.

Imran’s brother in-law Ben Goldsmith was married into the Rothschild family, one of the richest and most powerful families in the world.

As cricket spread to the smaller towns and villages of Pakistan, players from all walks of life and a vast variety of back grounds appeared on the scene; most importantly, the talent pool had become much larger.

A new generation of Pakistani idols exploded on the scene, some of them came from humbler backgrounds, but under Imran’s watch, they grew into a well groomed bunch of men, extremely confident — on and off the pitch.

The 90’s produced arguably Pakistan’s most talented cricketers, but while their predecessors had reached fame by causing great upsets and winning against the odds, the skilled cricketers that Imran Khan left behind never produced the results that were desired from them.

A team full of individual brilliance was found wanting as a unit. Infighting that had always existed in the Pakistani team had dropped to an all time low. And, unfortunately, the plague of match fixing had also seeped into the Pakistani dressing room.

The epidemic of high treason found Pakistani colours up for auction one too many times.

By the turn of the millennium, after match fixing investigations in the summer 2000, Mushtaq Ahmed, Wasim Akram, Waqar Younus, Saeed Anwar and Inzamam-ul-Haq had all been financially reprimanded by Justice Qayyum, with life bans on Salim Malik (who was at the end of his career) and Ata-ur-Rehman (who was not a permanent member of the team).

In the longer run, the financial punishment for these mega-stars was too insignificant to put a dent in their bank accounts and past accolades for Pakistan too valuable for the nation to forgo.

While a larger part of the populous continued to portray them as heroes, a significant number of people targeted them as villains.

But almost everyone had lost the blind love and trust the Pakistani cricketers always enjoyed.

It was a generation of match winners that brimmed with confidence and had experienced the high flying life of international cricket stardom.

Out of pure art and genius they registered some memorable wins during the decade and their fame and fortune continued to grow.

While their popularity and fanfare was at an all time high, the very fabric of the sport was being diluted at its roots.

Out of all the ills and malignancy the Pakistani dressing room went through, it was the loss of faith in their intent that had reduced their infallibility to suspicion in the eyes of their followers, and more importantly, in the minds of their own team members.

The Holy Quran was brought out and the entire team took an oath of loyalty to the Green flag, before every game.

After Pakistan’s abysmal World Cup performance in 2003, Chief Selector Aamir Sohail, one of the witnesses in the Qayyum Report dropped all the prominent names from the squad, making fellow whistle blower Rashid Latif captain.

However, Inzamam-ul-Haq soon returned to the team, with his senior teammates all gone, he was captain as last resort. This marked the start of a new era in Pakistan cricket.

Earlier, Saeed Anwer had joined the Tableeghi Jamaat after losing his young daughter to cancer. Now, Pakistan’s new captain also turned to the Jamaat looking for answers.

Perhaps in an attempt to not just find direction but also 'cleanse' what had previously passed through the corridors he led his men into.

A new breed of Pakistani cricketers was nurtured under the guidance of Inzamam.

Regular congressional prayers were held on the outfield and a separate room was usually reserved in hotels of touring cities, serving the purpose of a mosque.

From marijuana smokers on Caribbean beaches to a team full of practicing Muslims, Inzamam had not just seen the long journey unfold in front of him but had steered it in the direction it had taken.

While most of Inzamam’s team followed him, there were still those who had been a part of the Wasim Akram generation, highly social and integrated into the cultures that they interacted with.

Shoaib Malik played with Wasim Akram at PIA and then made his ODI debut under Akram in 1999. In a strong and long batting line, Malik was slotted to bat at No.10 in his first outing.

Shoaib Akhtar remained the bad boy of Pakistan cricket even under Inzamam’s captaincy.

Mohammad Asif was also to follow Akhtar’s route, involved in constant controversies and always getting into trouble off the field.

His affair with Pakistani TV star Veena Malik made headlines, especially when she claimed that Asif had taken money for his car and never paid her back.

“He would get drunk and thrash me. There have been occasions when the next morning, oblivious of everything, he would ask, ‘Maine lagaya kya yeh zakhm’ (have I given you these bruises)?

“On another occasion, he hit me hard when the food that I had prepared for his friends wasn't sufficient. I told him, ‘Sirf aadha ghanta doh, main aur khaana bana deti hoon’ (just give me half an hour and I will cook some more food). He didn't listen to what I said and slapped me instead,” claimed Veena.

While exceptions like Shoaib and Asif existed within its ranks, a larger part of the Pakistani team was polarised into right-wing fanaticism under Inzamam.

Initially, the Pakistan Cricket Board saw the positives of the ideological shift in the Pakistani team, it later advised Inzamam to tone down the religious factor in the team.

As some players complained that they were being pressured by the skipper to join the Tableeghi Jamaat.

After retiring, Inzamam past the mantle to his fellow Tableeghi Jamaat recruit Mohammad Yousuf. But, very soon, half the team was fighting over captaincy.

Six players were reported for taking oath on the Holy Quran in Mohammad Yousuf’s hotel room that they would not accept Younus Khan as captain.

In 2010, captain Mohammad Yousuf and Younus Khan were banned indefinitely, Shoaib Malik and Rana Naved-ul-Hasan were banned for a year, while Shahid Afridi and the Akmal brothers were fined and placed on probation for six months.

Most embarrassingly, coach Intikhab Alam reported: “There is a mental problem with our players. They do not know that they are representing the country. They don't know how to wear clothes and how to talk in a civilised manner.”

The team was in shambles, not just on the field, but also off it. And, the worst was still to come.

In 2010, a media sting operation uncovered the faces of some of Pakistan’s best talent.

Convicted of spot fixing, the Pakistani captain Salman Butt, ace fast bowler Mohammad Asif and budding young paceman Mohammad Amir were put behind bars in the United Kingdom.

Misbah-ul-Haq took charge of the Pakistani team at its lowest point and steadied ship gracefully. However, the damage to the Pakistani team would leave its scars for time to come.

The last truly star-studded Pakistani team took the field with Wasim Akram leading the way and the left arm fast bowler feels that his long locks had not just added to his persona, but also his performance.

“We wanted to tell the players through Nabila’s — a renowned stylist — lecture how to present yourself as a person which is very important for international players as they are ambassadors of the country.

“A good hairstyle and good dress add to your confidence and it can play a very good role in giving someone much-needed confidence. As a person you need to look presentable, which I feel has been missing in some of our players.” said Akram.

Team Misbah gave some great results in Test cricket, perhaps over achieving and surprising everyone, given the resources at disposal.

But their approach was visibly timid, they lacked the glitter and glamour the Pakistani Team was once famous for.

A large part of the general fan base yearned for the flamboyance and craved for the swagger that Pakistan cricket once was.

Pakistan cricket team was now finally devout of superstars, barring one.

The last of the enigmas of the 90’s era, Shahid Khan Afridi has been adored by the Pakistani public like no other.

Of ‘Wasim Akram’s men’, he was the youngest and brattiest; he grew up like the spoiled child of a fallen kingdom.

No rules applied to him, and he followed none.

While Afridi was a product of an era of flare and flamboyance, he was also as much a part of Inzamam’s team of religious redemption.

In fact, he was their regular ‘Imam’, often leading the congregational prayers.

Afridi has led a colourful life on the cricket field, off it, he has had a stable and conservative family. He has four daughters and a wife who takes a veil.

After Afridi’s ODI retirement there appears to be a void of stardom in the Pakistani team.

Though Afridi continues to play T20 Internationals but the low frequency of these fixtures indicates the near-end of Pakistan team’s last surviving celebrity.

Among the current lot, Ahmed Shehzad and Umar Akmal are the two cricketers who appear to have a liking for glitter and glamour more than their peers.

But, are they seen as the new style icons in Pakistan?

Umar Akmal was locked up by the police after getting into a brawl with a traffic warden in Lahore. Later, a ‘sessions court’ in Lahore issued arrest warrants for Umar not appearing in the court.

Both Ahmed Shehzad and Umar Akmal have been dropped from the squad after the World Cup. According to reports their attitude needed improvement. The same could be said about their modeling skills as well.

As Pakistan was on the brink of being knocked out of the World Cup, the fake twitter account of Big Nas, kept the Pakistani public entertained with its command over the English language.

At the age of 20, Nasir Jamshed was put behind bars after being caught cheating in a ninth grade English exam. He was later released on Rs 20,000 bail.

Pakistani cricketers have gone from being the most loved, adored and aspired men in the country to being the laughing stock of the nation, not just on the field, but off it too.

And the ODI whitewash against Bangladesh has not done their popularity any favours either.

It seems, even today, cricket heroes of the past, at the age of 62 and 48 respectively, Imran Khan and Wasim Akram were the more eligible bachelors than most of the current cricketers.

Pakistan has been a country with a shrinking middle class population, deteriorating educational systems and an economy where over 60 per cent of the population has gone under the poverty line (if $2 per day is taken as minimum wage, in line with international standards for middle income countries).

There has been a steady deterioration of the gentry that runs Pakistan; the politicians, bureaucrats, government banks, airline carriers and most other civil service institutions.

And, the Pakistan Cricket Board is no exception.